Placing geology at foundation of essential discoveries

March 29, 2024 | Carleton College

by Daniel Myer

Above: Professor Bereket Haileab leads a geology field trip in 2023.

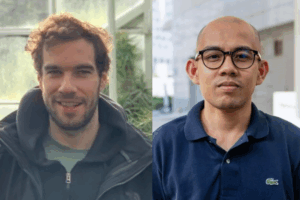

Bereket Haileab, MS'88, PHD'95, chair and professor of geology at Carleton College, is a researcher and teacher animated by his passion for geology.

Bereket Haileab

Haileab has been a cornerstone of geology at Carleton College, a small, private liberal arts college in the historic river town of Northfield, Minnesota, since he joined the faculty in 1993. Through his research over the years, he has also helped rejuvenate the study of the guiding principles behind his discipline, and connected that work with the larger Northfield and Carleton communities. His experiences, ranging from studying Rice County’s hydrology to helping chart the founding story of the entire human species, have revealed the role geology plays in multiple major disciplines. Today, he teaches these lessons to new generations of students, and shows that the College’s geology department is a true testament to the quality of a Carleton education.

At first, Haileab’s work had a utilitarian angle. After his undergraduate education at the University of Addis Ababa in Ethiopia, he had the opportunity to study for his PhD with well-known geochemists at the University of Utah. “There,” Haileab said, “I got the skills to do chemical analysis, interpret the results, and write about it.”

These experiences solidified his background in geochemistry, petrology, and mineralogy, which Haileab used to become an exploration geologist with the Geological Survey of Ethiopia. In his role, Haileab surveyed regions of western Ethiopia to find new gold deposits. Although he found the chance to apply his skills in chemical analysis fulfilling, he was interested in getting more involved with the interdisciplinary field of paleoanthropology — the study of human evolution through fossils, cultural artifacts, and more — which his graduate school experiences had introduced him to.

“When I came to Utah, I went to the field every summer and met many [experts in paleoanthropology] there and in meetings,” Haileab said. “My research was used in every place.”

Those who study the origin of the human species, like paleoanthropologists, depend on extensive geological research. With a lot of their modern work based on the fossils of early people or closely related species, scholars and scientists also need those fossils’ detailed geological contexts, including the current state and geologic history of their dig sites. After all, Haileab said, “you don’t find fossils floating by themselves.”

In 1985, Haileab joined a University of Utah research group working in Kenya, where just one year prior, the “Turkana Boy,” a Homo ergaster, was discovered. Haileab’s group needed to map the surrounding Turkana Basin in order to refine the dating process that allowed geologists and paleoanthropologists to prove that the Turkana Boy was 1.6 million years old. Haileab’s research, however, expanded far beyond one basin.

“We found that the volcanic ash from Turkana, to the sediments of the Red Sea cores, to the sediments in the Gulf of Aden, all the way south to Lake Albert in Uganda, to Ethiopia… was all formed originally [in the Turkana Basin], which makes it the most important point,” Haileab said. “For most of the fossiliferous [fossil rich] sediments, we could correlate all of the sedimentary basins and all of the findings temporally.”

Read the entire article at Carleton News.