King of the Playa

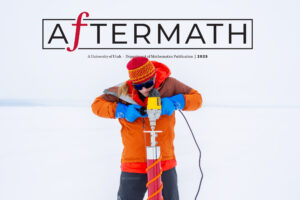

On a crisp October morning, Kevin Perry pedaled his bike across the Great Salt Lake playa, trailing a machine that tests how much wind energy it takes to disturb the crust and move dust across the surface. Colleagues jokingly call him the “king of the playa” because he’s spent so much time here, testing different patches of the lake surface for toxic metals and trying to understand the recipe for dust storms.

Declining water levels exposed much of the Great Salt Lake's bed and created conditions for storms of dust laden with toxic metals that now threaten 2 million people. Parts of the Great Salt Lake hardly resembled a lake at all this fall.

Water levels in October fell to the lowest levels on record, exposing much of the lakebed and creating conditions for storms of dust — laden with toxic metals — that now threaten the 2 million people living nearby.

Rio Tinto Kennecott smelter.

Researchers are racing to understand this new hazard, which adds a new layer of air pollution concern for the Salt Lake City area and threatens to dismantle the progress made to improve air quality in a region where oil refineries, a power plant and a gravel mine are part of the city skyline and the surrounding mountains trap pollution. In neighborhoods on the city’s historically redlined west side, lake dust is raising concern in areas that have experienced decades of environmental disparities and the most vulnerable people some days struggle for a breath of clean air.

“We have 2.5 million residents along the edges of the lake,” said Kevin Perry, a University of Utah atmospheric scientist researching the Great Salt Lake dust. “These dust plumes come off and make the air unhealthy regardless of what’s in it.”

But even those in wealthy enclaves away from the most visible sources of pollution won’t be spared from the dust. New research suggests arsenic-rich concentrations of dust from any source are the highest in wealthy Salt Lake area communities and that fast-growing suburbs could face the brunt of the dust storms’ impact.

Scientists want to understand how much risk the dust’s toxic metals pose to humans, what level of exposure is unsafe and what the implications for Utahans could be over time. No matter what they find, it’s a threat that will only continue to grow as lake levels drop.

On the lakebed

When the wind picks up, the playa surface can start to feel like a sandblaster. Perry's first fat bike, with 4-inch thick tires wide enough to move across sand, lasted about 750 miles before it gave out, corroded by salt.

In the course of researching the Great Salt Lake dust, Perry was forced to abandon a bike in mud, peppered by hail during a lightning storm, and heard bullets whizzing past his head, fired by an illegal target shooter.

Molly Blakowski, doctoral student.

Molly Blakowski, a doctoral student and dust researcher at Utah State University who regularly hiked a 20-mile loop of the playa to collect dust samples, said she would never venture out with less than 4 liters of water. Some moments, it can be hard to see more than 20 feet ahead.

“Everything turns into a mirage,” she said of long research days spent “trapped in your own thoughts.”

In October, water levels on the Great Salt Lake dropped to all-time lows.

Once lively marinas are now dry and empty of sailboats. Brine flies — fundamental to the food web — are disappearing because the water has become so salty. Mining companies applied to dredge longer canals so they could reach water with their equipment.

The lake’s volume is down at least 67% since pioneers once settled in the valley. Humans are responsible for about three-quarters of its decline, according to research from Utah State University. The megadrought roiling the western United States is responsible for the rest of the deficit, which has left more playa to explore.

What some might view as a flat, static environment is actually changing dramatically in front of Perry’s discerning eyes. In one recent research project, he cycled 7 miles several days a week, visiting 11 sites on each trip. One week, a site would be a raised mound of sand and dust. The next week, it could be a hollowed-out depression.

Retreating water levels on the Great Salt Lake.

During dust storms, host spots on the lake will pop and emit swirls of dust, collecting particles less than a fraction of the width of a human hair, darkening the sky and propelling them into communities nearby. The smallest particles can remain airborne for weeks at a time.

The lake bed contains pollutants like arsenic, distributed widely across the surface, which could be an indication that some of it occurs naturally, Perry said.

The lake has long been a catchment for industrial pollution. Each area of the lake has its own recipe of toxic metals and other substances, fed by different polluting industries nearby. Researchers are concerned that what’s been stored in the lake will soon be carried on the wind into Salt Lake City and other neighboring communities.

About 9% of the lakebed was a dust source as of 2018, he said. A protective crust covers other areas of the lake, but it’s being broken down by wind and weathering.

“The longer the lake bed is exposed, we expect that to increase. It could increase to 24% to 25% of the lakebed,” Perry said.

This isn’t a problem caused by climate change; Utahans are simply consuming too much water for agriculture, industry and residential use from the overtaxed rivers that feed the terminal lake. Modeling suggests human water diversion has reduced the lake level by about 11 feet, the Utah State research shows. Meanwhile, increased evaporation due to climate change has caused the lake level to drop less than half a foot.

Lawmakers in Utah — the “industry” state — have begun to turn their attention to the lake, passing a series of bills designed to revamp how the state uses its water. Utah Gov. Spencer Cox in November closed the basin to new water appropriations. But for years, the lake was an afterthought in the state’s unslakable thirst for economic growth.

“The entire state has an unhealthy relationship with water,” Perry said. “We need to start living like we live in the desert.”

Researchers still don’t understand exactly where the dust ends up, whether its toxic metals are being easily absorbed into people’s bodies and what risks that might pose. To try to answer some of those questions, scientists with the U.S. Geological Survey in 2018 and 2019 installed 18 dust traps throughout the Salt Lake City area.

The traps were left out for months and captured everything: dust from the lake, from local construction and from nearby deserts.

When they examined the dust, researchers found some interesting storylines.

“We’ve got some bells going off,” said Annie Putman, a USGS hydrologist who led the study. “The pieces are there to think we should be concerned.”

Traces of arsenic, lead and other toxic metals were discovered across the sites, according to the findings, which were published in the journal GeoHealth in late October.

At every site, concentrations of arsenic were enough to exceed an Environmental Protection Agency marker of concern for residential soil. One site had a concentration 35 times higher, though it’s not clear how that translates to risk for human exposure.

The Bowl

Salt Lake City, often associated with ski slopes that gleam above the city skyline, developed a reputation for air pollution long before dust grew as a concern. Of 888 U.S. metro areas, it ranked the ninth-highest in an EPA risk screening that modeled health risk from toxic chemical releases in 2020, and 20th for short-term particle pollution last year by the American Lung Association.

The pollution burden is felt unequally among residents.

John Lin, Atmospheric Research Professor.

Mountains cradle Salt Lake City on three of its sides. Its fourth border — to the west — leads to the brackish-smelling shores of the Great Salt Lake. Interstate 15 slices the city in half, dividing east from west. On the east side, well-to-do homes sprawl toward the canyons, gaining in elevation.

Housing in neighborhoods that make up the “west side,” as Salt Lake residents call it, commingle with refineries, a wastewater treatment plant, highways, railways and a busy airport. The neighborhoods are typically less wealthy, less white and historically redlined — the west side was deemed a “hazardous” real estate investment in the 1930s by the federal Home Owners’ Loan Corp.

These neighborhoods are closer to the valley floor, where the lion’s share of the air pollution can be found.

“If you look at Salt Lake, it’s essentially a bowl and the dense emissions are in the lower elevations,” said John Lin, an atmospheric research professor at the University of Utah.

And with the exception of ozone, pollutants such as black carbon, nitrogen dioxide and particulate matter “tend to be higher in lower-income neighborhoods, places with nonwhite populations,” Lin said.

In summer, concern centers on wildfire smoke and ozone. Spring and fall were once respites. But now, those seasons are turning to dust.

In the winter, the word “inversion” is a dirty word for Salt Lake residents. During an inversion, a layer of warm air settles over the valley like a lid for the bowl, trapping everything below as if it were a cap.

Daniel Mendoza, assistant professor of atmospheric sciences.

“The pollution builds up a hot spot and doesn’t blow away,” said Daniel Mendoza, an assistant professor of atmospheric sciences at the University of Utah.

Neighborhoods higher in elevation — more often above the inversion’s cap — are typically less impacted as pollution builds. But on the west side, closer to many sources of pollution, residents can get stuck in a thicker pea soup of car exhaust, refinery emissions and other pollutants.

“It irritates the eyes and gives me sinus infections,” said Jorge Casillas, 58, who has lived on the west side for 15 years. “It’s hard to be trapped in the valley.”

Overall, emissions have improved in Salt Lake City, mostly because of vehicle emissions standards enacted by the Obama administration’s EPA, according to Perry. The EPA in 2021 proposed re-listing the Salt Lake City area as in “attainment” for small particle pollution it had been failing to sufficiently control.

“When we switch to electric vehicles, our air quality is going to improve dramatically,” Perry said.

But wildfires and dust storms off Great Salt Lake are erasing the progress that has been made. For those in the West Side, it adds a new layer of concern for their health.

“There’s so much sediment and so much trapped for so long. It’s pulling up stuff that’s been trapped for 100 years,” Casillas said. “Are there carcinogens or other health risks? That’s what I’m worried about. There’s so many children in the neighborhood.”

A drumbeat of media coverage over dust and pollution has frightened some Utahans.

“I’ve received a number of emails from concerned citizens reconsidering living in Salt Lake City,” said Janice Brahney, an assistant professor at Utah State University’s watershed sciences department.

"We don’t know"

When USGS researchers mapped the samples collected from their dust traps, they found something interesting.

While other metals such as nickel, thallium and lead were more likely to exceed those EPA markers in poorer, less-white communities like Rose Park, arsenic was more concentrated in samples from wealthy communities, possibly because of its past use as a fertilizer on agricultural lands.

The researchers suspect that urban, diverse neighborhoods are receiving much of their dust and the toxic metals within that dust from local sources — nearby polluters or construction projects. It’s also possible that dust from the Great Salt Lake and other nearby playas picks up local pollutants from nearby mines, refineries and pesticides as dust travels into the city.

Meanwhile, researchers found the highest levels of dust — and metals — in suburbs outside urban Salt Lake City. Researchers suspect communities north of the city, including areas such as Syracuse, Ogden and Bountiful could be receiving the majority of the dust that blows off the lake. In early October, less than a mile from what was once lakeshore, workers were hammering away to frame new housing.

These areas are an air monitoring dead zone, Perry said.

“There’s almost no sampling done north of Salt Lake City,” he said. “We’re really lacking a coherent network to answer the question of who is impacted the most.”

Annie Putman, USGS researcher.

Putman and colleagues this year set up another 17 dust traps — all nicknamed “Woody” — in counties north of Salt Lake to better evaluate the risk for those areas.

So much remains unknown. While the EPA has screening levels for metals in soil, no environmental standards exist for exposure to toxic metals contained in dust.

“How much arsenic does there have to be over a 24-hour-period for dust to cause problems — we don’t know. We don’t have any study that can tell us that,” Putman said. “What are the short- term or long-term consequences of that? We don’t know at all.”

Researchers are also unsure if the arsenic and other metals in the dust are “bioavailable” — meaning they can be absorbed into plants, animals and humans. Testing is ongoing. Blakowksi is growing cabbage in a laboratory and sprinkling the plants with dust samples from the Great Salt Lake to see how much arsenic they take up.

In California, ratepayers have spent about $2.5 billion controlling dust emissions on Owens Lake, which was drained by the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power only to become the biggest humanmade source of dust in the U.S..

Researchers say the Great Salt Lake represents a much larger threat.

“The area of currently exposed lakebed is over seven times larger than the entire area of Owens Lake,” Blakowski said, adding that the population downwind is about 50 times larger in Utah’s case. “We can’t wait. It’s just going to keep getting dustier and there are serious human health and ecosystem implications if we sit on this too long.”

Images and story by Evan Bush, first published @ NBC News.