Gentrification drives patterns of alpha and beta diversity in cities

April 18, 2024

Photo: Mountain lion in the Wasatch Mountains. Credit: Austin Green.

Over the past two decades, a return of investment and development to once-neglected neighborhoods has meant a significant increase in spending on restoring parks, planting trees and converting power and sewer easements into publicly accessible greenspaces.

That trend — sometimes called “green gentrification” — tended to raise property values, helping to price out many neighborhoods’ original inhabitants. That led to an obvious question: What had those changes done to local animal populations, and what might that say about the changing dynamics of how nature functions in American cities?

This requires a staggeringly complicated analysis, and a new study published earlier this week in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), a vast and diverse array of data includes nearly 200,000 days of camera trap surveillance, taken over three years across almost 1,000 sites in 23 U.S. cities each with a unique mammal population, pattern of urban development and interaction between the two.

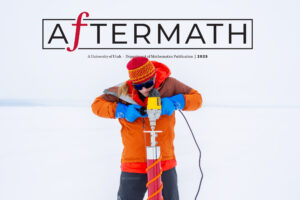

Austin Green, PhD

Some of that data have been accumulated by conservation ecologist Austin Green, a post-doctoral researcher and Human/Wildlife Coexistence stream leader in the acclaimed Science Research Initiative (SRI) at the College of Science. Leveraging the citizen science movement in the intermountain region, Green and his SRI team played a critical role in assembling a cohesive, detailed data-driven narrative of how gentrification — when lower-income people are forced out from American neighborhoods — the animal populations in the areas they’re leaving behind shift toward local species less typically associated with city environments. In turn, this phenomenon adds to the larger conversation in the U.S. about the reach and complexity of racial inequity.

Green's research is part of a monumental effort to collect and interpret data that have global implications about how humans and wildlife co-exist, especially in this case, as it relates to the continuing gentrification of cities, where more than 58 percent of the world population lives. Informed by Green's work in the SRI program combined with that of many others', scientific breakthroughs, as illustrated in the PNAS study, can directly influence conservation and adaptive management strategies.

Students in this particular stream at the U learn about wildlife ecology and conservation, as well as how to conduct ecological fieldwork, design complex studies of animal behavior and human-wildlife coexistence, curate and format large scale-datasets, and conduct advanced statistical analysis.

You can read the full article by SAUL ELBEIN in The Hill about this fascinating research and its findings published in PNAS here.