Airborne Spores—the spread of fungal pathogens

February 5, 2026

Above: Jessica Brown, speaker at Science@Breakfast

Jessica Brown started her Science@Breakfast talk January 29, 2026 with a simple task she asked of the audience—take a single deep breath.

After the collective room inhaled and exhaled, Brown quickly mentioned, "And now I will let you know that you have each inhaled up to ten fungal spores."

Fungi are everywhere. In our soil, in our bird feeders, and—as demonstrated above—in the air we breathe. Brown reassured us that the vast majority of these interactions are harmless. But, there are some species of fungi that can spell danger.

Brown has been studying fungi for many years beginning as an undergraduate at Pomona College where she studied fungal genetics. But, eventually this interest evolved into her research on fungal disease. She has been doing work at the U since 2014 but was recently recruited to join the School of Biological Sciences as an associate professor where her work has continued.

Of the three to ten million species of fungi only 200-300 have the ability to infect a mammalian host. Cryptococcus neoformans (C. neoformans), as a budding yeast, is one such species that has caused high mortality.

Infection begins when an inhaled spore enters the lungs and bursts within them. A healthy immune system usually employs T-cells and quite easily gains immunity to the fungal infection. But, for those who are immunocompromised a different story plays out.

Titan cells

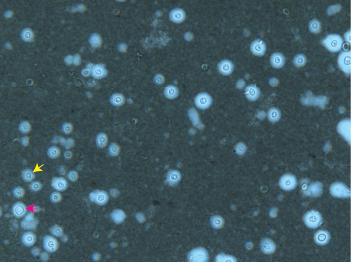

When T-cells get depleted, infection gains a foothold. At this point, the fungi which began as small budding yeasts form enormous "Titan Cells" of at least 20 microns in diameter. Amazingly, these cells which were initially haploid, containing only one copy of its genome, can gain up to 360 copies of its genome during this growth process.

Titan cells are proficient at surviving in the lungs but struggle to expand beyond this realm. Over time this opportunistic pathogen begins to produce smaller haploid "seed cells" of about five microns which can spread throughout the central nervous system and into the brain. This idea, hypothesized by Brown in 2022, was a breakthrough in the dissemination of C. neoformans.

This is where C. neoformans becomes highly dangerous. It can develop fungal meningitis which has a mortality rate of 100% if left untreated and a mortality rate of 30-70% if treated. By comparison, bacterial infections have a death rate from three to five percent. Globally, C. neoformans causes 200,000 deaths annually and roughly 56% of this number are patients diagnosed with HIV left untreated.

a mortality rate of 100% if left untreated and a mortality rate of 30-70% if treated. By comparison, bacterial infections have a death rate from three to five percent. Globally, C. neoformans causes 200,000 deaths annually and roughly 56% of this number are patients diagnosed with HIV left untreated.

But, once C. neoformans infects its mammalian host it is unable to spread from person to person. In Brown's own words, infecting a mammalian host is an "evolutionary dead end".

So, how does it spread to so many people?

Accidental pathogen

Rather than spreading from host to host, the spore has to spread throughout the environment as an "accidental pathogen." Essentially, environmental conditions need to be ideal for its growth.

To understand this phenomenon it's important to look at Coccidioides, also known as Valley Fever. It originated in the Four Corners region in the American southwest where warm and dry conditions allow for its growth in desert soils. In fact, medical students were once taught that people are not likely to contract this infection beyond this region.

However, Brown told the audience at the Natural History Museum of Utah that things have drastically changed due to climate change: "It has expanded beyond the Four Corners region and this unfortunately does include Utah… I would be shocked if it were not in the Salt Lake Valley right now."

C. neoformans can be found in our soil and even bird guano—which makes birds a potential vector of infection. For this reason, Brown began to swab bird feeders and—in collaboration with U colleagues Sarah Bush, Nikolas Orton and Amy Buxton—the birds themselves.

She found that bird feeders easily support a thousand or more fungi which is more than the birds themselves.

"Our working hypothesis right now is that the birds are carrying fungi, but the fungi are growing, and potentially have been subjected to selective pressures on the feeders themselves."

Brown suggested to the audience that if you have a bird feeder you should wear gloves when you change it. If you don't, you could be exposed to a fungal pathogen. She also mentioned that she soaks her own bird feeder in a 1:10 bleach solution roughly once a month.

Fungal pathogens are a fascinating realm of study. High levels of mortality, novel methods of dissemination through Titan and seed cells, and environmental risk factors such as climate and bird guano add layers to the complexity. But, through years of research and dedication Brown has uncovered and decoded some of the mechanisms which are foundational to the spread and efficacy of C. neoformans.

And given that Brown is now on faculty at the U, it's very likely that more mysteries will be uncovered—leading us closer to curing a pathogen which kills hundreds of thousands of people every year.

A collective exhale of relief may be in order.

by Nathan Murthy