‘The elephant in the room’ for sciComm

August 5, 2025

Above: Assuming the position for your daily dose of science communication

Scientists are crucial voices in the public debate about wicked problems — societal-scale, high-stakes issues with no clear solutions, like pandemics and artificial intelligence. In the past, experts reached the masses through journalists at traditional news outlets.

Today, science discourse happens online, where science content competes for attention with posts from influencers, advocacy groups, conspiracy theorists and other unverified sources.

One wicked problem, COVID-19, highlighted how ill-prepared scientific institutions are to utilize modern media effectively. The struggle to adapt is partly due to social media platforms preventing meaningful research, according to a new article.

“So many people are getting information in current online environments, including on social media. Not studying these platforms is not an option,” said Isabelle Freiling, assistant professor in the Department of Communication at the University of Utah and co-author of the article. “If we know how people make sense of information in those spaces, then we can use that to communicate science towards those realities. But if we don’t get access to the relevant social media data, it’s just a guessing game.”

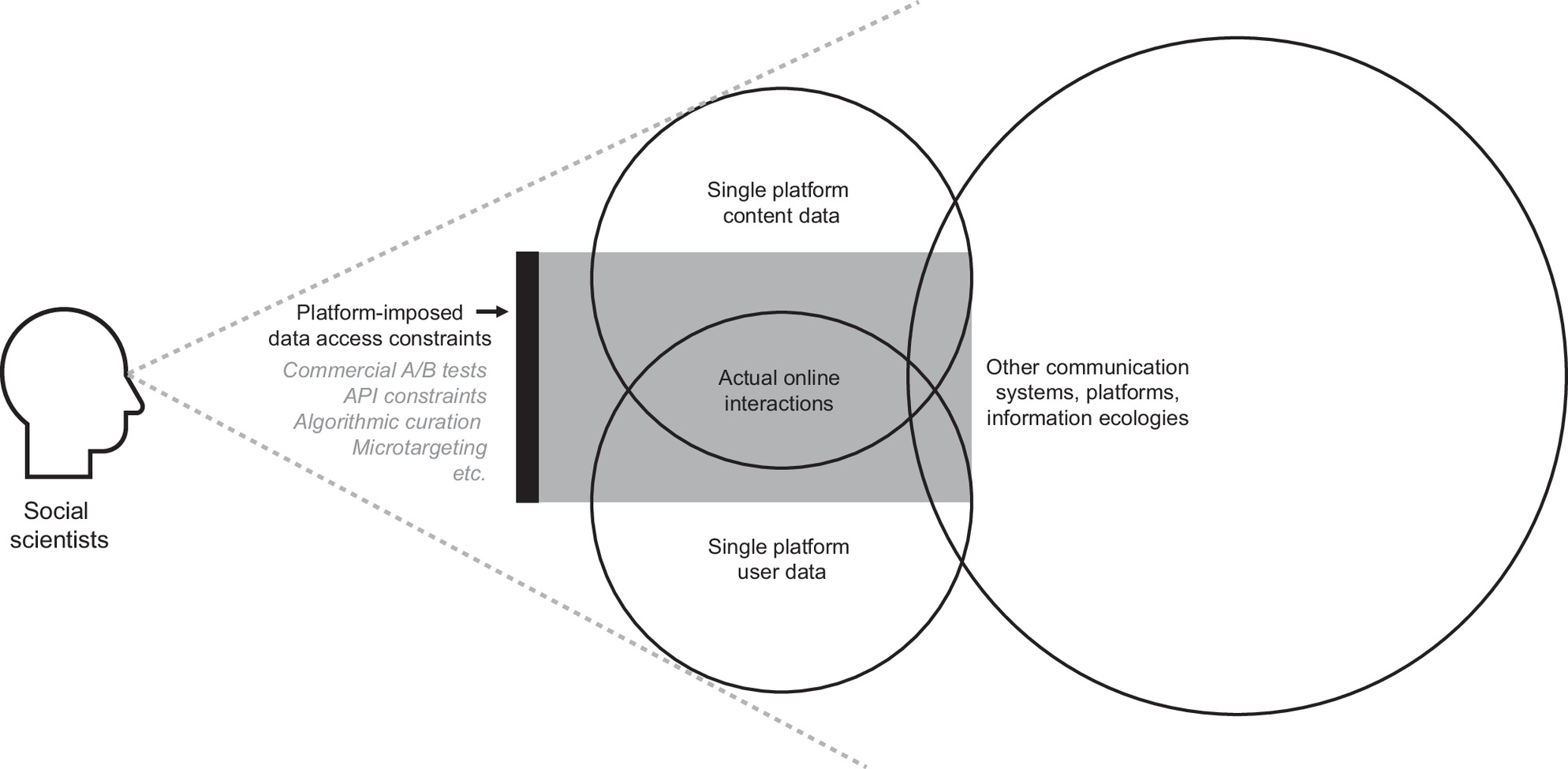

Without buy-in from social media companies, researchers can only access limited data using tools like application programming interfaces (APIs). APIs act as intermediaries that fulfill information requests, for example, “Find all posts with keyword ‘AI.’” This method rarely captures the full picture because platforms pre-process and shape the data in unknown ways. Academia-industry collaborations can yield more complete datasets, but these partnerships have built-in conflicts of interest.

“We as a scientific community need to address the elephant in the room: Are we really finding true results here? Or are we finding what platforms wants us to find?” said Freiling. “Social media companies have all the power over what data they give to researchers. We would never accept such conflicts of interest in research in the pharma or tobacco industry.”

Moving forward, the authors call for a reimagining of science communication and research, which will require a deep commitment to changes within science itself.

“The scholarly community lacks clear guidelines for evaluating the academic value of those social media collaboration studies that give access to otherwise inaccessible data, while at the same time sacrificing control over to the platforms. That needs to change,” she continued.

The article, published on June 30 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, lays out the unique challenges for science communication arising both from the technology landscape itself and from factors of use, ownership and regulation in an evolving media environment.

A pathway forward

Communication doesn’t happen in a vacuum. In mere seconds, science content must draw in multitasking, doomscrolling audiences while gaming secret algorithms that decide what users will see.

“The algorithms on social media prioritize content that gets people’s attention, and often times our scientific messages aren’t crafted to be very attention grabbing,” said Freiling, who is also a fellow at the U’s One-U Responsible AI Initiative. “Focusing on communicating science accurately is not enough to reach people.”

Establishing evidence-based guidelines for communicating science on social media should be a priority for the scientific community, the article states. This requires an empirical approach to understanding audiences, crafting messages, mapping communication landscapes and most importantly, evaluating the efficacy of communication efforts.

Read the full article by Lisa Potter in @The U.